Recently, a book was released, and on its first page readers learned this: “My name is Julie Yip-Williams. I am grateful and deeply honored that you are here. This story begins at the ending. Which means that if you are here, I am not. But it’s okay.”

“The Unwinding of the Miracle: A Memoir of Life, Death, and Everything That Comes After” by Yip-Williams is about how the 42-year-old self-described “writer, mother, wife and lawyer” died of Stage IV colon cancer in March 2018. It’s crucial to note that Yip-Williams listed “writer” first, because it was through her WordPress blog that she rediscovered how powerful writing could be throughout what she called her “cancer fighting journey.” Many of her posts have titles taken from classic literature, including the famous poem “Invictus” and William Wordsworth’s phrase “splendor in the grass.” Despite severe vision challenges (she was born with congenital cataracts and deemed legally blind), Yip-Williams remained a lifelong reader, one who believed in the power of words to communicate with others.

Her book, which documents her life from Stage IV diagnosis when she was 37 to her tragic death just five years later, moves back and forth between her dire present and her past—including a childhood that was almost more tragic. Born to an ethnic Chinese family in civil war-torn Vietnam, Yip-Williams recounts how her grandmother encouraged her parents to seek “endless sleep” for their unseeing infant. Fortunately, the herbalist they asked to euthanize the young Yip-Williams flat-out refused to comply. When she was just 4, her family took one of the last boats out of Saigon to reach the United States.

The irony, you see, is that while Julie Yip-Williams is busy, very busy, with the business of dying, through her determination to reach out to others, she communicates many lessons in how to live, how to be a good human being, how to fully inhabit one’s days on this earth. In a letter to her daughters Mia and Isabelle (a chapter called “Life”), Yip-Williams writes that despite the sadness she knows they will experience, she hopes they will: “Live a life worth living. Live thoroughly and completely, thoughtfully, gratefully, courageously, and wisely. Live!” Read an excerpt from Julie's book.

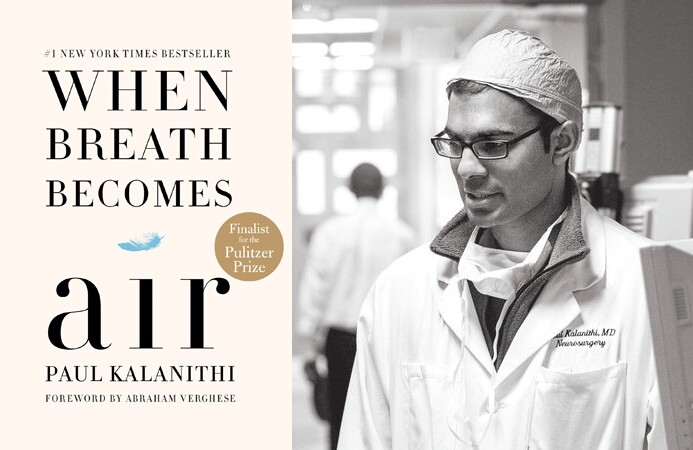

Lessons about living abound in “The Unwinding of the Miracle,” but also in other memoirs about the process of dying. Paul Kalanithi and Abraham Verghese’s “When Breath Becomes Air” follows 36-year-old neurosurgeon Kalanithi and his struggle and eventual death from Stage IV lung cancer. He wanted to confront the question of what makes life worth living in the face of death—and he knew that while his own death (in 2015, while he was still working on this memoir, hence Verghese’s involvement) would come sooner rather than later, he also recognized that every human being has to grapple with the same dilemma. We are here, alive, and one day we will die. How should we live?

In “The Bright Hour: A Memoir of Living and Dying,” Nina Riggs—also in her late 30s when diagnosed with breast cancer, which quickly turned terminal—takes that question and condenses it into making life as meaningful as possible within a limited time. Rest assured this is no sugarcoated tale of a model cancer patient; Riggs tells the truth about her treatment. As she writes in her prologue, “There are so many things that are worse than death: old grudges, a lack of self-awareness, severe constipation, no sense of humor, the grimace on your husband’s face as he empties your surgical drain into the measuring cup.”

While Yip-Williams, Kalanithi and Riggs all faced gruesome symptoms, treatments and procedures, Irish filmmaker Simon Fitzmaurice may have had the most challenging time writing about his. “It’s Not Yet Dark: A Memoir” covers from 2008, when Fitzmaurice learned he had amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS/Lou Gehrig’s Disease), to his death in October 2017. Not only did the author choose a controversial path to prolong his life, but he and his wife also chose to conceive the youngest two of their five children having the knowledge their father would never live to see them grow up. Read an excerpt from Simon's book.

It’s not important that you know everything about where I come from. About who I am. It’s not important you know everything about ALS, about the specifics of the disease, about what it’s like to have it. It’s only important that you remember that behind every disease is a person. Remember that and you have everything you need to travel through my country.

Each of these brave and talented men and women has wisdom to impart about the process of dying, especially important in our Western culture that often draws an opaque curtain between the dead and the living. But more important, each of them also has a great deal of wisdom to share about the process of living. These four books are quite different and bear reading separately, yet they also have some congruence. Here is a set of 10 lessons they share.

1. Maintain an attitude of gratitude. In the heart-wrenching afterword of her husband’s book, Lucy Kalanithi shares how, in the short time after Paul chose to remove the respiratory equipment keeping him alive, he wanted to hold their baby and express gratitude to his family. Those of us who remain breathing will find this does us a world of good.

2. Love the ones you’re with. Perhaps, like Fitzmaurice, you have a passel of children and a devoted spouse. But even if your inner circle is just you, a few close friends and your cat, you can strengthen those bonds and make your chosen family a close family.

3. Choose your own adventures. Yip-Williams spends a chapter detailing the solo trips she’s taken around the world, emphasizing that even with her vision challenges, she cherishes the sense of being alone in the face of grandeur or finding her way through a crowded city marketplace.

4. Never stop learning. Reading Kalanithi’s book is a journey into remarkable intelligence, and from his enthusiastic account of his mid-residency study of neuroscience, it’s evident that even in the midst of illness, new ideas excite him.

5. Appreciate your senses—and the sensual. Fitzmaurice drily explains, when asked about the children he and his wife Ruth conceived as he grew weaker, “My willy still worked.” A cold drink, a warm bed, the scent of roses—these experiences are heightened for people who know their time is limited. Why not take time to smell the roses now?

6. Occasional indulgences are healthy. Briggs likes to spend time, when possible, with her husband, another couple and “a playmate of ice and some handles of liquor and a party sampler of Pepperidge Farm cookies, and John deejays us through eighties and nineties dance grooves on his cell phone, and we pretend we are childless.” She was ill; maybe you’re not. Indulge in a treat. No one will tell.

7. Forgiveness is even healthier. Kalanithi says he returned to “the central values of Christianity—sacrifice, redemption, forgiveness—because I found them so compelling.” He found forgiveness necessary, because as a surgeon, he saw himself and colleagues make life-altering mistakes. Try the easier “Sorry, honey” while you still can.

8. No one has the wheel. Control is an illusion, as Yip-Williams notes in her chapter “Fate and Fortune.” She had been so concerned with the universe’s plan that she “had discounted the importance of free choice.” This is something we can all exercise, as long as we remember we’re not in charge of things like disasters or illness.

9. The world doesn’t stop. At Fitzmaurice’s sister’s wedding, “I dance for the last time.” He would never wish to write that sentence, but he knows it’s a fact. His children grow, his films win awards, the sun spins across the sky—and he’s still dying. We all are. It’s a necessary thing to acknowledge and accept.

10. You are enough. Briggs quotes Michel de Montaigne: “The illness pinches us on one side; the remedy on the other.” No life is perfect, no treatment certain, but each individual consciousness, like each individual snowflake, is different and beautiful